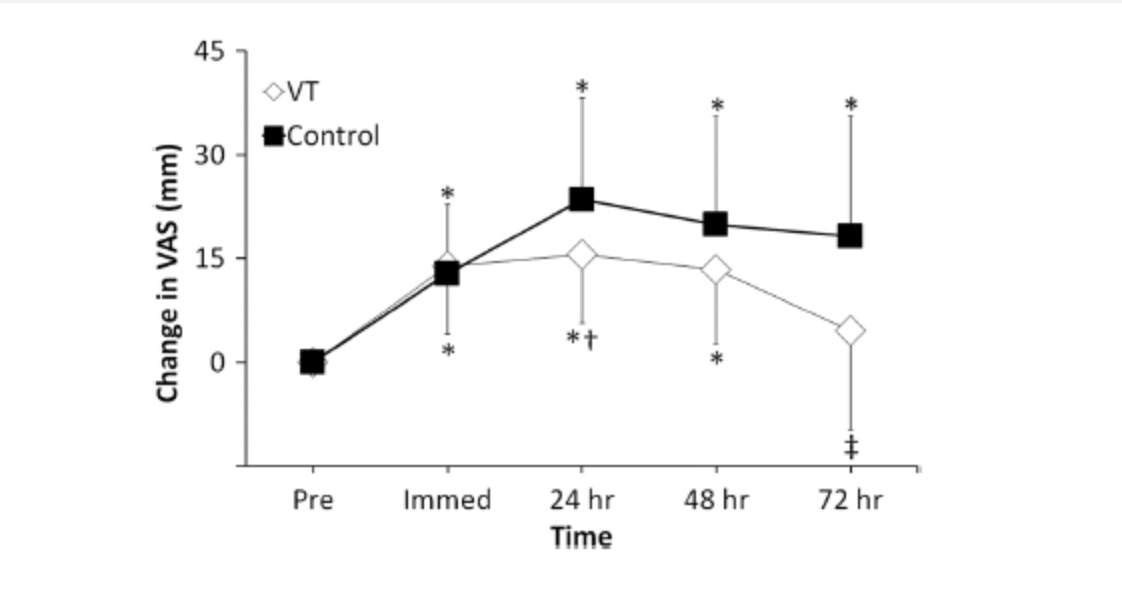

Indices of maximum strength may not provide enough detail about muscle-tendon loading at submaximal levels, nor have the ability to grade muscle recruitment or appropriately timed patterns of activation according to the required task. This is especially true in a painful state, as noted previously by both Hodges and Richardson, and Wadsworth and Bullock-Saxton. Brox et al noted participants with rotator cuff tendonopathy were 15% stronger in measures of abduction on their asymptomatic side than controls and comparable in strength to controls on their symptomatic side, a phenomenon has also been seen in lateral epicondylosis in a study by Bisset et al. The problem with simple assessments of strength is that maximum strength measures may not reflect the complex interaction between excitatory and inhibitory influences on the motor command that occur during tasks. Movement patterns are influenced by motor control changes that include both peripheral and central contributions. Papers by Rio et al, Weier et al, and Goodwill et al point to an imbalance between the excitatory and inhibitory influences over muscle activation around the painful tendon. The functional result seems consistent with a protective adaptation that reduces the mechanical demands placed on the tendon, that is, an apparently protective adaptation.

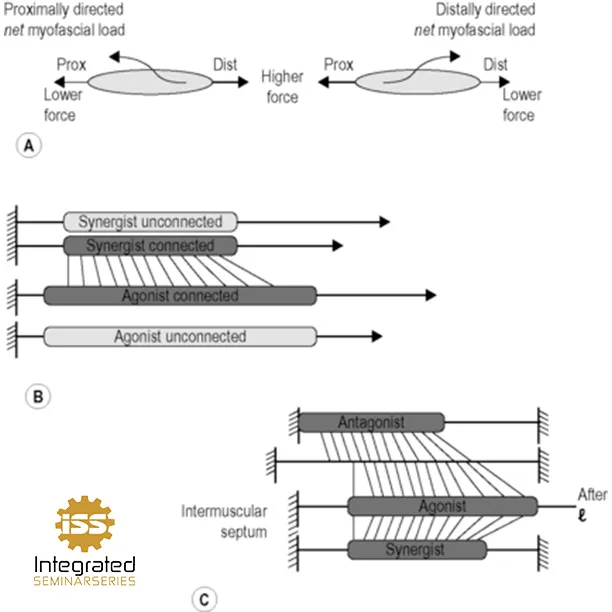

Regardless of whether motor control changes are a cause of pain or epiphenomena, changes to motor control may not just be bilateral but system wide. There is an increasing body of evidence that multiple sites are frequently affected due to complex intrinsic and extrinsic factors, and contralateral pathology and/or the development of symptoms is common. That is to say that once tendon pain (or pathology) is established at one site, there appears to be the potential for increased risk of tendonopathy elsewhere according to Mokone et al and September et al.

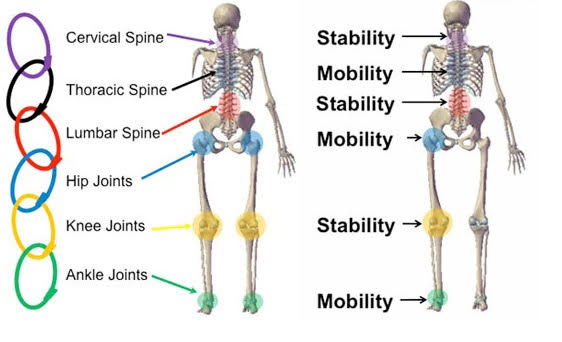

The take-home message here is that we need to assess movement, and not just at the site of pain. A global movement-based examination that assesses every region, in all planes of motion, is required. However, if the therapeutic intervention does not match the metrics you collect, this carefully collected data will go to waste.

Identify the aberrant movements.

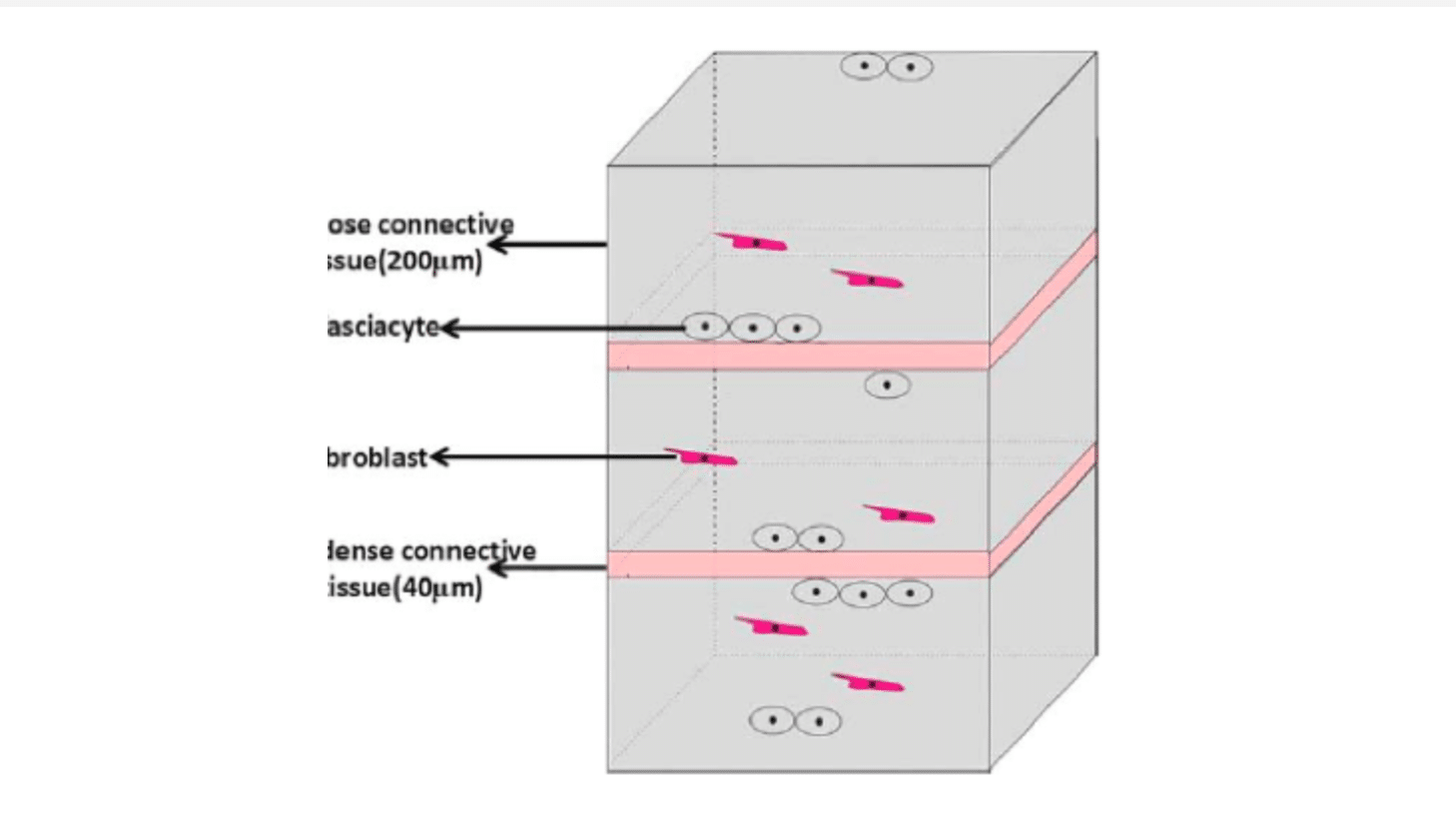

Isolate the nature of these deficits and the tissues responsible.

Integrate the neurological and myofascial systems to grove proper movement patterns.